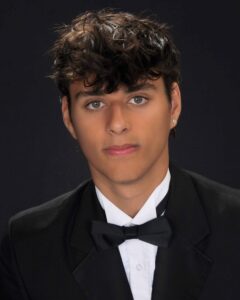

Name: Itai G Hershko

From: Oceanside, New York

Votes: 0

One Second

I failed my driver’s test. Twice.

The first time, I panicked during parallel parking and jumped the curb. The second time, I rolled through a stop sign while checking my rearview mirror, convinced someone was about to hit me. My instructor sighed and said, “You’re overthinking it.”

He wasn’t wrong, but he also wasn’t right. I wasn’t overthinking the rules. I was thinking about my cousin Caleb.

Two months before my sixteenth birthday, Caleb rear-ended someone at a red light. He was tired and trying to skip a song on his phone. The cars were totaled. He ended up in the hospital with a concussion and two broken ribs. The other driver had a toddler in the backseat. They were okay, but Caleb still has nightmares.

I could have done the exact same thing.

At the time, I didn’t admit that out loud. I acted cautious, followed every rule, drove like someone twice my age. My friends teased me, my mom asked if I was traumatized. But the truth was, I was scared. Not just of driving, but of how easy it is to do the wrong thing even when you know better.

And then, I proved myself right.

One afternoon during senior year, I was driving my cousin to soccer practice. We were running late, and I was stressed. My phone buzzed with a text from my girlfriend. Without thinking, I looked down for a second and drifted halfway into the next lane. A truck honked. Frightened, she looked at me and said, “Didn’t you say phones were dangerous?”

That moment hit me harder than Caleb’s accident because it wasn’t someone else who could have made a dangerous mistake. It was me.

That’s when I realized something most teen drivers understand but few adults seem to get. Knowing the rules isn’t the same as applying them when it matters. Teen driver safety is a public issue not because teens don’t care, but because we’re still learning how to manage attention, emotion, and judgment, all in real time, behind the wheel.

Traditional driver’s ed doesn’t really prepare us for that. It focuses on laws and maneuvers, which are important, but it rarely addresses what actually causes teen crashes. Distraction, peer pressure, anxiety, and overconfidence. It treats everyone the same, when in reality, we’re all learning to drive under very different conditions.

I have ADHD and Sensory Processing Disorder. That means I process stimuli differently. Driving for me isn’t just multitasking; it’s sensory overload. The traffic, the sounds, the lights, the movement can become disorienting fast. But none of that ever came up in driver’s ed. I had to figure out strategies on my own. Structured routines before driving. Music that calms instead of distracts. Mirror settings that reduce visual clutter.

When I realized how much of driver’s education was missing, I decided to do something about it.

I started a peer-led driving safety group at my school. It wasn’t formal at first, just casual conversations after games, during lunch, in the parking lot. But people showed up. And they talked. About the time they almost ran a red light because they were distracted. About driving after a late shift because they didn’t want to say no to a ride request. About pretending to be confident behind the wheel even when they were scared.

We didn’t lecture each other. We listened. We shared strategies. We talked about managing real-life driving challenges, not just textbook ones.

We also talked about being neurodivergent drivers. Teens with ADHD, autism, and anxiety shared the unique challenges they faced and the strategies they’d found that actually worked. Some used calming playlists. Others put their phones on airplane mode. A few of us created pre-driving routines, like athletes before a game, to get in the right headspace. None of that came from a textbook. It came from each other.

The biggest thing I’ve learned is that teens don’t need to be scared straight. We need to be taken seriously. We’re not dangerous because we don’t care. We’re dangerous because we’re still developing, still learning, and still being taught the wrong way. If we shift from fear-based instruction to education that reflects our realities, we can change the outcomes.

I’m proud that the club I started will continue at my high school even after I graduate. I’ve trained two underclassmen to lead the meetings, and our faculty advisor is committed to supporting the program long-term. I want to carry that same spirit into college. This fall, I plan to bring the peer-led model to my university. The stakes are even higher there. Students drive longer distances, often late at night, under more stress. We need these conversations more than ever.

Caleb’s accident changed the way I drive. But my own mistake changed the way I think about driver education. One second of distraction can change everything. But one honest conversation, the kind that treats teens like people instead of problems, can start to change the culture.