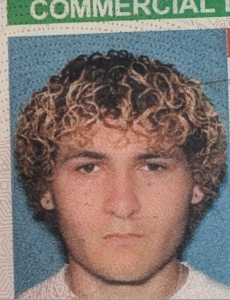

Name: James Dickens

From: Iowa City, IA

Votes: 0

You’re Lying: Thoughts from your Local Bus Driver

I’m a bus driver. For two years, I’ve been a driver for one of the oldest student-run bus network in the country, CAMBUS at the University of Iowa. When I finished training, and could tell people I was a bus driver at 18 years old, the reaction was usually shock.

“You drive buses? At 18?”

“That must be scary! I hope you’re getting paid well..”

And my personal favorite:

“You’re lying.”

That last one came from an old friend who needed video proof of me driving, before finally admitting that he had just never considered someone as young as me could drive a bus.

I think there’s two stigmas contributing to this kind of disbelief, and I promise, I’m getting to the driver education part of this essay. The first is excusable, in that most people’s only experience with buses comes from school, whose bus drivers tend to be on the older side. City buses, I’ve found, have a healthy mix. The second stigma is what I’m writing about today.

Physically, a bus commands your attention, whether viewing from inside or outside your car. Most transit buses are 40ft, longer than an RV and some yachts. It’s shaped like a pinewood derby car that a boy scout forgot to carve and flies around tight city streets, weaving through parked doordash drivers like a bull rampaging through a china shop, but somehow leaving everything intact. They’re slow, bulky, and loud but somehow smooth to ride.

The trick to all this, I’ve discovered, is practice. The magic is that bus drivers drive in a circle. That’s it. The same circle, over, and over, and over, and over. For years. Every curb, every zone of braking, even regular pedestrians can play out in a driver’s mind like the memorized sheet music of a stage pianist. Some of my coworkers don’t, but I consider it an art.

Practice is why CAMBUS can throw 18 year olds on a bus and have them navigate rush hour traffic with 70 passengers and wiggle through fencing in construction zones without getting down on time. In some cases, new employees train for months before they’re considered responsible enough to handle their own route. We’re made sure we understand the gravity of driving a bus, both of the safety of our passengers and the safety of the road. We’re shown what happens when a bus and a car butt heads: the bus always wins.

The more comfortable I became driving a bus, the more scary driving a car started to feel. After months of training, I still only drove the same streets, on buses checked by professional mechanics regularly, with a dispatcher available constantly if anything ever went wrong. I was happy to be trained so thoroughly… but it almost didn’t feel like a big deal anymore. Then I step into my car. No dispatcher, no route, new streets. No one follows me cautiously like they do a bus, and I technically have the freedom to drive anywhere. I need to figure out new signage myself without a team safety meeting, and can go up to 65 miles an hour legally.

In my state, teens are allowed to get a driving permit as early as 14 years old. They’re expected to listen only to the guidance of their parents who haven’t been taught road safety in 30 or 40 years, and after all of that, only go through a couple weeks of driver’s ed before being given the “green light” to drive wherever they desire. Talking to a non-bus driver reminds me how little we prepare drivers for the road. Something that I could lose my job over is a forgotten driver’s ed factoid to most, and unlike me, the worst punishment they’ll get is a passive aggressive explanation of what yielding to the left means from myself.

That is, until a snarky pep talk isn’t the worst punishment they’ll get. Until passing a stopped car in a pedestrian crossing zone at 40 miles an hour gets a National Guardsman weeks away from retiring killed, as was the case 2 years ago right in front of my house. We learn about something in bus training called the hierarchy of mistakes, which is similar to the hierarchy of needs. It goes like this:

The foundation of the pyramid is based on “at-risk behaviors.” These would be things like glancing at your phone, in-attentiveness in busy areas, or not checking your blind spots. If these behaviors happen, say, a few thousand times over the course of your life, maybe only a few hundred would result in a “near miss,” the next step of the pyramid. Slamming on your brakes to avoid a bicyclist you didn’t see at a crosswalk, swerving around an obstacle because you were tailgating, just anything that doesn’t actually cause damage. Out of these few hundred dodged bullets, maybe a few dozen would turn into “incidents,” like trading paint with a sign or bumping into a bollard. Still, not too bad. Only a handful of incidents turn into accidents. Rear-ending someone at a stoplight, t-boning at an intersection, or knocking a cyclist off their bike. It’s only a handful of times, but what is built on minor, almost imperceptible bad habits have now led to someone, maybe even yourself, getting physically injured.

Out of these handful of accidents, it only takes 1 making it to the top of the pyramid to break a community. To end an entire family, kill a young person’s shot at life and land yourself in a cell. Glancing at your phone ONCE while driving could get someone killed. Mistakes of some kind are bound to happen, but the entire pyramid is built on repeated, risky behaviors. It sounds scary, and it did to me, at first. I came to see this fact as relieving, actually. I can completely eliminate the chance of getting someone injured while driving if I just… don’t practice behaviors that can lead to an accident.

Such a simple fact going undertaught to young drivers is infuriating. My friends will make fun of my driving, asking if fully stopping at all stop signs and checking my blind spots before every merge or driving exactly the speed limit are just habits from driving the bus. Sure, I’ll get fired for breaking these rules, but the rules are in place so I don’t kill someone. I don’t want to kill someone driving a bus and I don’t want to kill someone driving a car. In fact, I’m hoping to go my whole life without doing so in any capacity. We forget that our cars weigh up to three or four THOUSAND pounds regularly moving faster than a cheetah can sprint. We forget that people’s lives are literally at stake, and the details matter. There needs to be much more awareness of the common, small mistakes that young drivers often make. Usually, it has to do with looking at your phone while driving, reckless driving, and drunk driving. We’re lazy trying to correct these mistakes, we’ll say things like “be part of the fight against drunk driving” or have a bumper sticker that says “no phone zone.” Yes, these are important concepts, but the details are so important giving teens their introduction to driving. Teach them how to sync their phones to their infotainment systems so they can answer important texts by voice. Have them practice telling an insistent drunk friend they can’t drive, and teach them about ways to get home if no one is sober. These details obviously take more time than the previous way of doing things, which also included 3,000 teen driving fatalities per year. I think a person’s life is worth a whole lot more than a detail.