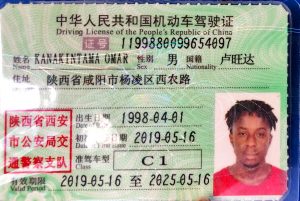

Name: Kanakintama

From: China, Sinchuan

Votes: 0

Driving

NAME:

KANAKINTAMA OMAR

Q1-1. Besides

bandwidth and latency, what other parameter is needed to give

networks? Please list them and give their defines. Which parameter is

good characterization of the quality of service offered by a network

used for (i) digitized voice traffic? (ii) video traffic? (iii)

financial transaction traffic?

A1-1:

(i) digitized

voice traffic:

The digitized

voice traffic requires the parameters other than the bandwidth and

latency is the Real-time delivery of the data with high Throughput.

Real-time

delivery:

It is an on-time

and a uniform delivery of packets between the sender and the receiver

in the network. The packets must transfer with uniform time.

Throughput:

The Throughput is

defined as the number of packets that are transferred in a period of

time

(ii) Video is

quickly becoming one of the most effective ways to drive floods of

targeted traffic directly to your blog, sales pages and other online

offers. Unfortunately, most people have failed to grasp how to use

video properly. Fears of being in front of the camera, or overcoming

technological hurdles quickly debilitate most marketers from taking

action. Video does work and it doesn’t have to be difficult,

expensive or time-consuming.

Q1-2: What are

two reasons for using layered protocols? What is one possible

disadvantage of using layered protocols? What difference and

similarity are between the OSI TCP/IP reference models from view of

techniques?

A1-2: What are

two reasons for using layered protocols?

Modularity, and

easier testing.

What is one

possible disadvantage of using layered protocols?

That kind of

depends on the protocols. If you carry out the technique of layered

protocols too far, it gets very slow and inefficient.

What difference

and similarity are between the OSI TCP/IP reference models from view

of techniques?

The OSI model is

a VERY layered design. The problem is that with this level of

layering, it gets very slow…

And though the

layers are fine by themselves, nobody uses the inbetween layers… so

they are a burden due to the separation.

TCP/IP was

implemented as a working design. It has layers, but those layers that

were split out in the OSI model are merged – as they are tightly

related, and don’t need to be separated.

As I recall, the

OSI model was developed without the use of a working implementation,

so it was a more theoretical approach that did not have a working

reference implementation.

The TCP/IP

approach was done by engineers implementing a partial design, then

seeing if that worked; then adding to it.

By the time an

integrated test was done, it was using 2.4 kbit/s (roughly 2400

baud), and would send roughly one character of data per second from

place to place (it had to echo the character back from the remote

node and each packet had the headers and checksums to send and

receive)… and as I remember reading, failed after about 2 bytes

were exchanged – but did demonstrate that it worked.

P1-1: TCP/IP

network byte order is big-endian used by some machines. However,

other machines use an inverse byte order (little-endian). Therefore,

any kind of machine is about to convert the local byte order of

numerical fields into network order. Generally ,the socket APIs

provide some functions which convert a unsigned short or long from

host(TCP/IP) to TCP/IP (host) network byte order (which is

big-endian), such as htons, htonl,ntohs, ntohl. In this practice, you

should use C language to implement the four functions and tests

without any system call related to network library. Finally, submit

the header, source files and test case.

R1-1: (Code in

header file, code in source files and test report)

9.12. htons(),

htonl(), ntohs(), ntohl()

Convert

multi-byte integer types from host byte order to network byte order

Prototypes

#include

<netinet/in.h>

uint32_t

htonl(uint32_t hostlong);

uint16_t

htons(uint16_t hostshort);

uint32_t

ntohl(uint32_t netlong);

uint16_t

ntohs(uint16_t netshort);

Description

Just to make you

really unhappy, different computers use different byte orderings

internally for their multibyte integers (i.e. any integer that’s

larger than a char.) The upshot of this is that if you send() a

two-byte short int from an Intel box to a Mac (before they became

Intel boxes, too, I mean), what one computer thinks is the number 1,

the other will think is the number 256, and vice-versa.

The way to get

around this problem is for everyone to put aside their differences

and agree that Motorola and IBM had it right, and Intel did it the

weird way, and so we all convert our byte orderings to “big-endian”

before sending them out. Since Intel is a “little-endian”

machine, it’s far more politically correct to call our preferred byte

ordering “Network Byte Order”. So these functions convert

from your native byte order to network byte order and back again.

(This means on

Intel these functions swap all the bytes around, and on PowerPC they

do nothing because the bytes are already in Network Byte Order. But

you should always use them in your code anyway, since someone might

want to build it on an Intel machine and still have things work

properly.)

Note that the

types involved are 32-bit (4 byte, probably int) and 16-bit (2 byte,

very likely short) numbers. 64-bit machines might have a htonll() for

64-bit ints, but I’ve not seen it. You’ll just have to write your

own.

Anyway, the way

these functions work is that you first decide if you’re converting

from host (your machine’s) byte order or from network byte order. If

“host”, the the first letter of the function you’re going

to call is “h”. Otherwise it’s “n” for “network”.

The middle of the function name is always “to” because

you’re converting from one “to” another, and the

penultimate letter shows what you’re converting to. The last letter

is the size of the data, “s” for short, or “l”

for long. Thus:

htons()

host to network

short

htonl()

host to network

long

ntohs()

network to host

short

ntohl()

network to host

long

Return Value

Each function

returns the converted value.

Example

uint32_t

some_long = 10;

uint16_t

some_short = 20;

uint32_t

network_byte_order;

// convert and

send

network_byte_order

= htonl(some_long);

send(s,

&network_byte_order, sizeof(uint32_t), 0);

some_short ==

ntohs(htons(some_short)); //